The Incandescent Wisdom of Cormac McCarthy

His two final novels are the pinnacle of a controversial career.

The Passenger and Stella Maris, Cormac McCarthy’s new novels, are his first in many years in which no horses are harmed and no humans scalped, shot, eaten, or brained with farm equipment. But you would be wrong to assume that the world depicted in these paired works of fiction, published a month and a half apart, is a cheerier place. “There are mornings when I wake and see a grayness to the world I think was not in evidence before,” The Passenger’s most jovial character, John Sheddan, says to one of several other characters who are suicidally depressed. “The horrors of the past lose their edge, and in the doing they blind us to a world careening toward a darkness beyond the bitterest speculation.”

McCarthy throws the reader an anchor of this sort every few pages, the kind of burdensome existential pronouncement that might weigh a lesser book down and make one long for the good old-fashioned Western equicide of McCarthy’s earlier work. At least when a horse dies, it doesn’t spend a week beforehand in the French Quarter musing about existence. For that matter, neither do most of McCarthy’s previous human victims, who were too busy getting hacked or shot to death to see the darkness coming and philosophize about their condition. To twist a line from the poet Vachel Lindsay: They were lucky not because they died, but because they died so dreamlessly.

McCarthy’s fervent admirers are bound to come to these novels with impossible expectations. The late critic Harold Bloom, who spoke for superfans of the writer everywhere, wrote that “no other living American novelist … has given us a book as strong and memorable as Blood Meridian,” McCarthy’s relentlessly bloody 1985 Western. That verdict came down back when Bloom favorites Thomas Pynchon, Philip Roth, Toni Morrison, and Don DeLillo still dominated the literary scene. McCarthy haters, equally passionate, find his writing mannered, his characters tediously masculine, and his plots—well, not really plots at all so much as excuses to find ever-fancier ways to rhapsodize about murder and carnage and the sublime landscape of the frontera.

The weirdness of McCarthy’s style is hard to overstate. He abjures quotation marks and most commas and apostrophes, so even his text looks denuded and desertlike, with the remaining punctuation sprouting intermittently, like creosote bushes. (I once compared an uncorrected proof of Blood Meridian with the finished book. I found that he’d struck just a couple of commas from the final text. That amused me: Looks good, McCarthy must have decided. But still too much punctuation.) His language is archaic. Characters speak untranslated Spanish and, in The Passenger, a bit of German. The omniscient narrator makes no concession to readers unfamiliar with 19th-century saddlery, obscure geological terminology, and desert botany.

The narration therefore registers as omniscient in both a literary and theological sense—a voice of a merciless God, speaking in tones and language meant for his own purposes and not for ours. He presides over the incessantly violent Blood Meridian and the only intermittently violent Border Trilogy of the 1990s (All the Pretty Horses, The Crossing, Cities of the Plain), and he delivers truths and edicts without any concern for whether members of his creation can understand them, though they are certainly bound by them. The language borrows heavily from the King James Bible, even when describing a bunch of unshowered dudes in Blood Meridian:

Spectre horsemen, pale with dust, anonymous in the crenellated heat … wholly at venture, primal, provisional, devoid of order. Like beings provoked out of the absolute rock and set nameless and at no remove from their own loomings to wander ravenous and doomed and mute as gorgons shambling the brutal wastes of Gondwanaland in a time before nomenclature was and each was all.

Here is McCarthy’s God: a deranged psycho who not only tolerates his world’s atrocities but conceives of them in these strange and inhuman terms.

For some critics, a little of this goes way too far. “To record with the same somber majesty every aspect of a cowboy’s life, from a knifefight to his lunchtime burrito, is to create what can only be described as kitsch,” B. R. Myers wrote in The Atlantic 21 years ago. He quoted a particularly wacky excerpt from All the Pretty Horses and remarked, “It is a rare passage that can make you look up, wherever you may be, and wonder if you are being subjected to a diabolically thorough Candid Camera prank.” Blood Meridian smacked the skepticism right out of me the first time I read it, but I have read it and most of McCarthy’s other novels again since, this time with skepticism reinforced. Was I in the presence of divine wrath, or being punked? I concluded that any novel whose diction conjures questions of theodicy as well as the ghost of Allen Funt has something going for it.

The novels McCarthy published in 2022, at the age of 89, permanently resolve the question of whether McCarthy is a great novelist, or Louis L’Amour with a thesaurus. The booming, omnipotent narrative voice, which first appeared in McCarthy’s Western novels of the 1980s and had already begun to fade in No Country for Old Men (2005) and The Road (2006), has ebbed almost entirely in these books—perhaps like the voice of Yahweh himself, as he transitioned from interventionist to absentee in the Old Testament. What remain are human voices, which is to say characters, contending with one another and with their own fears and regrets, as they face the prospect of the godless void that awaits them. The result is heavy but pleasurable, and together the books are the richest and strongest work of McCarthy’s career.

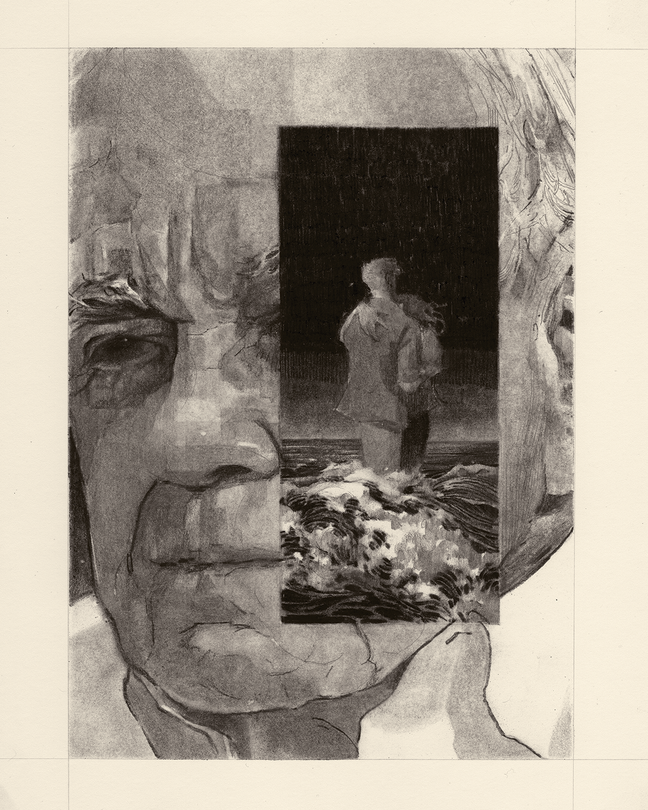

The plots are surreal, and the characters speak often of their dreams. The principal doomed dreamers in these novels are siblings whose formal education exceeds that of all previous McCarthy characters combined: Bobby Western and his younger sister, Alicia. Their father worked on the Manhattan Project, and for his Promethean sins the next generation was punished. Alicia and Bobby shared a vague, incestuous erotic bond and (even more deviant) the curse of genius.

Bobby, the protagonist of The Passenger, studied physics at Caltech but forsook science to race cars in Europe; after an ugly accident, he took up work as a salvage diver based in New Orleans. This novel, released first, is set in the early ’80s, some 10 years after Alicia killed herself. Stella Maris does not stand on its own and is best understood as an appendix to The Passenger. It belongs completely to Alicia and consists of a transcription of clinical interviews with a Dr. Cohen at a Wisconsin mental hospital shortly before her suicide. A math prodigy who studied at the University of Chicago and in France, Alicia left graduate training while struggling with anorexia and florid schizophrenic hallucinations. She is a key figure in The Passenger, too: Nine italicized sequences interspersed throughout Bobby’s story recount her conversations with a hairless, deformed taunter called the Thalidomide Kid, or just the Kid. The Kid acts as a ringmaster and spokesperson for a company of other hallucinatory figures. If this roster of dramatis personae is hurting your brain, then the effect is probably intended, because not one of the characters is psychologically well.

The plot of The Passenger is mercifully simple—and meandering, as McCarthy’s critics have complained of his books in general. Bobby is tormented by grief for having failed to save Alicia. His office dispatches him to search for survivors of a small passenger plane that crashed in shallow water. He finds corpses and signs of tampering. Someone got to the plane first. When he’s back on land, men “dressed like Mormon missionaries” track him down, interrogate him, and suggest that one of the plane’s passengers is unaccounted for. Their persecution intensifies, and Bobby (a quintessential McCarthy figure: laconic, cunning, prone to calamitous big decisions and canny small ones) spends the rest of the novel fleeing.

Bobby’s friends—chief among them the libertine fraudster Sheddan and a trans woman named Debbie, a stripper—are no less Felliniesque than the cast that appears in his dead sister’s hallucinations. Most of the novel is dialogue—if the thunderous omniscient narrator is listening, he’s not interested—and by turns tender, ironic, bitter, and searching. Debbie, like many characters in the novel, is literate and philosophical, and funny. She describes her heartbreak as she realized late one night that she was alone in the world. “I was lying there and I thought: If there is no higher power then I’m it. And that just scared the shit out of me. There is no God and I am she.” They are lowlifes and drunkards, but the sorts of lowlifes and drunkards who keep you lurking by them at the bar, even though you know they’ll rob you or break your heart. What will they say next? A line pilfered from Shakespeare or Unamuno? A revelation about the hereafter—or about yourself?

The Shakespeare is no coincidence—and of course Shakespeare, too, was weak on plot; as William Hazlitt and later Bloom affirmed, the characters are what matter. McCarthy’s Sheddan is an elongated Falstaff, skinny where Falstaff is fat, despite dining out constantly in the French Quarter on credit cards stolen from tourists. But like Falstaff, he is witty, and capable of uttering only the deepest verities whenever he is not telling outright lies. Bobby regularly shares in his stolen food and drink, and their dialogue—mostly Sheddan’s side of it—provides the sharpest statement of Bobby’s bind.

“A life without grief is no life at all,” Sheddan tells him. “But regret is a prison. Some part of you which you deeply value lies forever impaled at a crossroads you can no longer find and never forget.” The characters constantly tell each other about their dreams. Every barstool is an analyst’s couch, and every conversation an interpretation of the night’s omens. Sheddan’s response to the void, which he sees with a clarity equal to Bobby’s and Alicia’s, is to live riotously. “You would give up your dreams in order to escape your nightmares,” he tells Bobby, “and I would not. I think it’s a bad bargain.”

Alicia has no such wise interlocutors. Stella Maris is really an extended monologue, her shrink’s contribution little more than comically minimal prompts. (“I should say that I only agreed to chat,” she reminds him at the outset. “Not to any kind of therapy.”) Critics who have doubted McCarthy’s ability to write a female character must acknowledge that she is as idiosyncratically fucked-up as any of the protagonists in his previous oeuvre. If Sheddan is Falstaff, Alicia is Hamlet: voluble, funny, self-absorbed, and obsessed with the point, or pointlessness, of her continued survival. She is also completely nuts and, like Hamlet (whom she and Sheddan both quote, impishly and repeatedly), orders of magnitude too smart ever to be cured of what ails her. Bobby has a touch of Hamlet too, or possibly Ophelia—though his voyages into the watery depths are all round-trip.

Together they know too much, in almost every sense of that charged phrase. They know love, of a type one would be better off not knowing. Bobby has seen too much underwater. He and Alicia, cursed with a panoptic knowledge of science, literature, and philosophy, have reached a level of awareness indistinguishable from despair. The pursuit of Bobby by the mysterious Mormonlike men suggests that he has stumbled on forbidden facts (about criminals? extraterrestrials?). Alicia, too, seems to have arrived at certain bedrock truths about philosophy and math, and checked out of reality upon discovering how little even she, a woman of immeasurable intelligence, can understand. (Her trajectory mimics that of her mentor, Alexander Grothendieck, a real-life mathematician who gave up math, nearly starved himself to death, and became obsessed with the nature of dreams.) Her tone when speaking of the subject that once enthralled her is mournful. “When the last light in the last eye fades to black and takes all speculation with it forever,” she says, “I think it could even be that these truths will glow for just a moment in the final light. Before the dark and the cold claim everything.”

Long stretches of both novels involve discussions of neutrons, gluons, proof theory, and other arcana from modern physics and philosophy. One of the few points of agreement among physicists is that the world is stranger than humans tend to think, especially at extremes of size and time: What you see with your own eyes is definitely not what you get. The Passenger and Stella Maris treat that spooky observation and its implications with the reverence they deserve. No actual math intrudes, and the discussions of technical subjects is Stoppardesque—accurate and playful and accessible, and nevertheless daunting to readers unacquainted with surnames like Glashow, Grothendieck, and Dirac. (No first names are included, not that they would help anyone who needed them.) McCarthy’s books have always been intimidating, even alienating. Now it’s the characters, not the narrator, who do the alienating.

Alicia’s death is foretold on the first page of the first novel. Bobby’s is left ambiguous, and little is spoiled by my noting that time and space are pretzeled, that the nature of reality itself is suspect, and that he sometimes wishes that the car crash he suffered in Europe, just around the time when his sister was about to kill herself, had killed him rather than put him in a coma. “I’m not dead,” Bobby tells Sheddan, who replies, “We wont quibble.”

These novels are enduring puzzles. Several readings have left the nature of their reality still enigmatic to me. Any novels as suffused with dreams, hallucination, and speculation as the two of them are will invite doubt as to what is really happening. “Do you believe in an afterlife?” the psychiatrist asks Alicia. “I dont believe in this one,” she responds. Bobby and Alicia both have visions that call into question the nature of existence, and they are both fluent in the disorienting logic of the quantum-mechanical world. Having plumbed reality’s depths, they are not sure whether to come back to the surface to join those who live in the world of the normal, like Sheddan and his gang. By my second reading I started to feel like I had remained down there on the seafloor with them, in a state of meditative loneliness that no other book in recent memory has inspired.

Sheddan seems to have tasted that loneliness, and found existential solace in literature, even of the most savage sort. “Any number of these books were penned in lieu of burning down the world—which was their author’s true desire,” he says at one point, having just noted Bobby’s father’s role in building apocalyptic munitions. I wonder whether Sheddan is accusing his own creator here, and his tendency toward violence. McCarthy’s early southern-gothic period, comprising the four novels he published from 1965 to 1979, were Faulknerian, and at times darkly comic. Then came an even darker Melvillean middle, set in the Southwest and Mexico—nightmarish in Blood Meridian and romantic in All the Pretty Horses (1992)—and a desolate late period, with No Country and The Road.

Put another way, the early novels took place on a human scale, and Blood Meridian was about contests among humanoid creatures so violent and warlike that they might be gods and demons, a Western Götterdämmerung. The protagonist of the Border Trilogy was like a human on an expedition through this inhuman landscape. And the late novels featured humans forsaken by the gods and pitted against one another, or in the case of No Country, contending with demons and losing. McCarthy’s latest, and probably last, novels represent a return to human concerns, but ones—love, death, guilt, illusion—experienced and scrutinized on the highest existential plane.

I’m sure I wasn’t alone in wondering, on hearing the news of two forthcoming McCarthy books, whether they would be noticeably geriatric in their energy, with that spectral quality familiar from other late literary creations. (There are many counterexamples, of course: the silvery vitality of Saul Bellow’s Ravelstein, the comic bitterness of Mark Twain’s The Mysterious Stranger.) Such valedictory works are rarely among an author’s best. But as a pair, The Passenger and Stella Maris are an achievement greater than Blood Meridian, his best earlier work, or The Road, his best recent one. In the new novels, McCarthy again sets bravery and ingenuity loose amid inhumanity. In Blood Meridian, the young protagonist confronts a ruthless demigod and tells him off. In No Country, Llewelyn Moss beholds the inevitability of his own destruction and that of everyone he cares about, and shoots back at the demon who pursues him. The Border Trilogy is about a boy who leaves home and discovers, with equal parts courage and ignorance, a world harsher to his heart and body than he had known.

Now we see characters whose vision of the world is hideous from the start. And the grappling with this vision is more direct and more profound. The McCarthy of previous novels did not appear to have much of an answer to the question that his imagination invited, a question that goes back to the ancient Greeks: What does a mortal do when all that matters is in the hands of the gods, or, in their absence, no one’s? An almost-nonagenarian will of course think more acutely than a younger writer about fading from existence.

Just as Alicia imagines a final flickering glow of mathematical truth, Sheddan proposes to be a final holdout of humanism. He says he knows that Bobby has, like Sheddan, a heart whose loneliness is salved by literature. “But the real question is are we few the last of a lineage?” Wondering about the end of the age of literate culture, he tells his old friend, “The legacy of the word is a fragile thing for all its power, but I know where you stand, Squire. I know that there are words spoken by men ages dead that will never leave your heart.” These novels feel like McCarthy’s effort to produce such words, and to react to the dying of the light with Sheddan’s vigor rather than Bobby’s and Alicia’s despair. The results are not weakly flickering. They are incandescent with life.

This article appears in the January/February 2023 print edition with the headline “Cormac McCarthy Has Never Been Better.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.